Questions—On the Art of Greed

질문들—탐욕의 미술에 대해

Gimhongsok

Today, I’m going to talk about how we understand the concept of art. Since modern times, art has come to occupy its own independent territory, evermore expanding its functions and sphere, and in the process, has absorbed and incorporated other domains of culture. This has given rise to a strange situation: namely, as the tremendous integrative force of art has pushed out its bounds so far—as to include temporal art forms such as theater, film, and dance, and more reason-based disciplines such as philosophy, literature, and anthropology—the preservation of artwork in the “original” form has become an increasingly tricky task.

![]()

Separation of areas for the role of an artist

Question 1

Performance utilizing photography and video

Let’s first look at Marina Abramović’s performance art piece from the 80s. This work was represented by videos and photos. The idea that a performance could be collected did not obtain at the time, so material mediums such as video and photography stood in for the original work. For this reason, even though Abramović designated Rhythm 0 as a work of performance art, the museums that bought the work classified it otherwise. The collection record at the Guggenheim reads that while the tendency of Rhythm 0 is performance, its collection type is photography. Similarly, Tate labels the work as “72 objects and a slide projector with slides documenting the performance.”

![]()

GUGGENHEIM COLLECTION

Marina Abramović

Rhythm 0

ARTIST

Marina Abramović

b. 1946, Belgrade, Yugoslavia

TITLE

Rhythm 0

DATE

1975 (published 1994)

MEDIUM

Gelatin silver print with inset letterpress panel

DIMENSIONS

frame (photograph): 38 5/8 x 39 5/8 x 1 inches (98.1 x 100.7 x 2.5 cm); frame (text): 10 3/16 x 7 3/16 x 1 inches (25.9 x 18.3 x 2.5 cm)

CREDIT LINE

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Gift, Willem Peppler, 1998

COPYRIGHT

© 2018 Marina Abramović, courtesy of Sean Kelly Gallery/(ARS), New York

ARTWORK TYPE

Photography

MOVEMENT

Performance

![]()

Tate Collections

ARTIST Marina Abramovic born 1946

MEDIUM Table with 72 objects and slide projector with slides of performance and text

DIMENSIONS Overall display dimensions variable

COLLECTION Tate

ACQUISITION Presented by the Tate Americas Foundation. 2017

A performance can be collected in the form of videos and photos; granted, we cannot say that those are the original. They may represent the original, but that is a woefully inadequate representation. And this is not an issue of technology but one that is fundamentally irresolvable. Thus, artists have brought into art’s realm what cannot be preserved as art and obtained consent from all parties involved.

Museums began to collect performances as videos and photos and labeled them as such even when the artist specified their work to be performance art. Then, how do we differentiate between an artist who uses photography merely as a tool for documenting his/her performance and another artist who presents such documentation as a work of art in and of itself? Their performances are collected as photos—that goes for both artists. But if one artist claims that their original work is performance art and the other claims that, even so, the ultimate medium is photography, then should the collection records reflect the respective artists’ claims? I do think that both claims are legitimate. The medium of an artwork is determined by what the artist chose as their medium of expression. The reason why Abramović’s Rhythm 0 can’t be called photography is that Abramović decided that the work was performance art, not photography. Then why did she allow photos to serve as a proxy for her performance? And who decided this conversion of mediums anyway? Was it a shrewd new way of art collecting devised by then-powerful art museums? And has that since become a convention?

To sum up the questions: Are the photos at the Guggenheim documenting Abramović’s performance the original work? Or are they an archive collected for academic/educational purposes?

Question 2

Ethical Politics

Next, I would like to look at Shirin Neshat’s work. Neshat’s work arises from indirect criticism of social/political inequality and gender discrimination prevalent in Islamic societies and the absurdities of Iranian culture. In her photos and videos frequently appear Iranian women draped in chadors; Neshat uses them as material in her attempt to criticize the perceptive discrimination historically perpetrated against women. As we look at the Iranian people featured in Neshat’s work, immediately we get to wondering about a few things: Did those women in chadors participate because they met the desired conditions for their incorporation into Neshat’s art? Were they active participants who understood Neshat’s intents? Have they seen change in their circumstances since they appeared in her work? Do they know that Neshat’s work has gained international recognition? That the artist has earned great frame?

Despite Neshat’s political correctness, the question remains/ whether the people and their milieu adopted as material for promoting the very correctness truly function/ as independent subjects with agency. A distinction needs to be made between “those who participate in the production of an artwork” and “those who participate in an artwork.” The people who appear in Neshat’s work are not the crew hired for production but the cast. As the copyright on the work belongs to Neshat, the relationship between the artist and the cast could be formulated as an economic one by means of a wage or honorarium. However, in the event that the work achieves great acclaim, all the glory goes to the artist while the people who appeared in it see no change in their position, resulting in an unfair, hierarchical situation. The artist who created the work owns the copyright to it—legally speaking, there is nothing problematic about that statement. And yet it is troubling, ethically, and that is because the artist’s intellectual property was created collaboratively, involving many people, and through that property the artist gets to occupy a positon of great prominence.

The copyright on a performance that was conceived by an artist but completed by other participants nonetheless belongs solely to the artist, for the reason that the idea came from the artist. Here, do we classify participants who are specialists in certain fields as “employees” or “volunteers”? It would be hard to say unless there is a clear agreement reached between the artist and the participants. If they are considered employees and their expertise is of high caliber, then simply paying them hourly wages wouldn’t be fair. Does the notion prevail that the products of professional research, such as documentary films or anthropological photo records, are superior to the people who are featured in those products?

Affective labor is work carried out by managing one’s emotions and is a form of labor that is intended to trigger and expand interpersonal communication. Most of the performers appearing in Tino Sehgal’s work are professional dancers or ones with comparable skill. Besides demonstrating work ethic traits such as solidarity and teamwork, these performers as affective laborers function to expand human relationships, and as such, their labor is melded in their performances. Just as human actions could be instrumental, instrumental actions too have human aspects. Isn’t a major task of performance art bringing these human aspects to the forefront?

For videos and films featuring people, including documentaries, is it fair to grant the sole copyright ownership to the artist even when there were others involved who carried out affective labor? Legality aside, that is.

Question 3

Division of copyright

A few complications arise when a piece of performance art is performed not by the artist but by other participants. They could be ordinary people or specialists in specific fields. They may participate as collaborators or as temporary workers. Or they may be classified as volunteers and paid an honorarium for skills they exhibit. In some cases, instead of an honorarium, the payment could be made as a wage. Performing participants are not assistants or day laborers whose contributions have a material basis; rather, they provide affective labor through their bodily appearance and actions. If a performance like this becomes an object of commercial transactions through galleries, can we call it “merchandise”? Given that people can’t be merchandise, should we then consider the video documentation of the performance merchandise? Does the video have value as merchandise? How can performance art function as merchandise?

Artworks are at once public goods and merchandise: since when did we have this dual designation and through what process was that established? Can the concept of “public” be applied to art?

Question 4

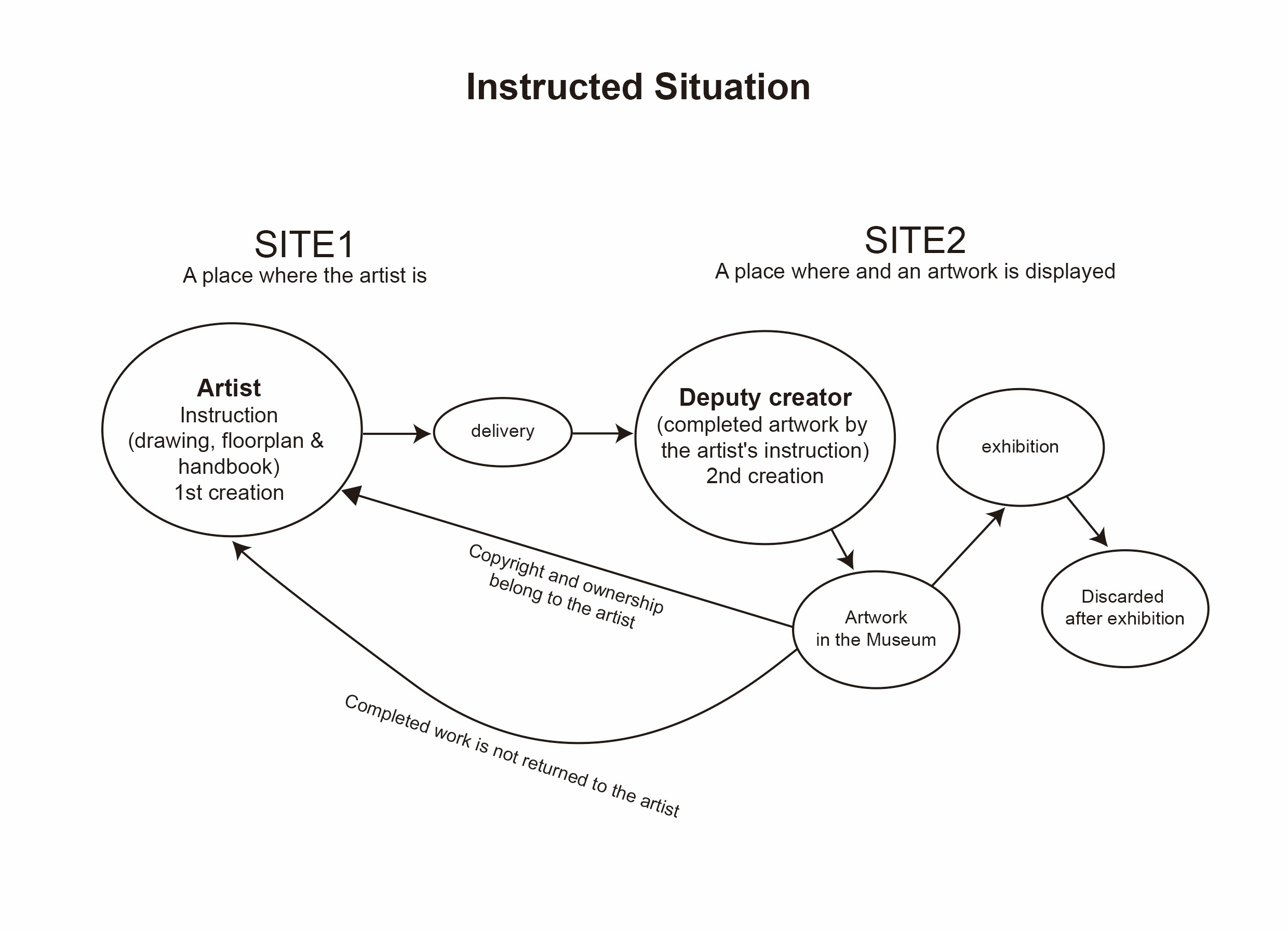

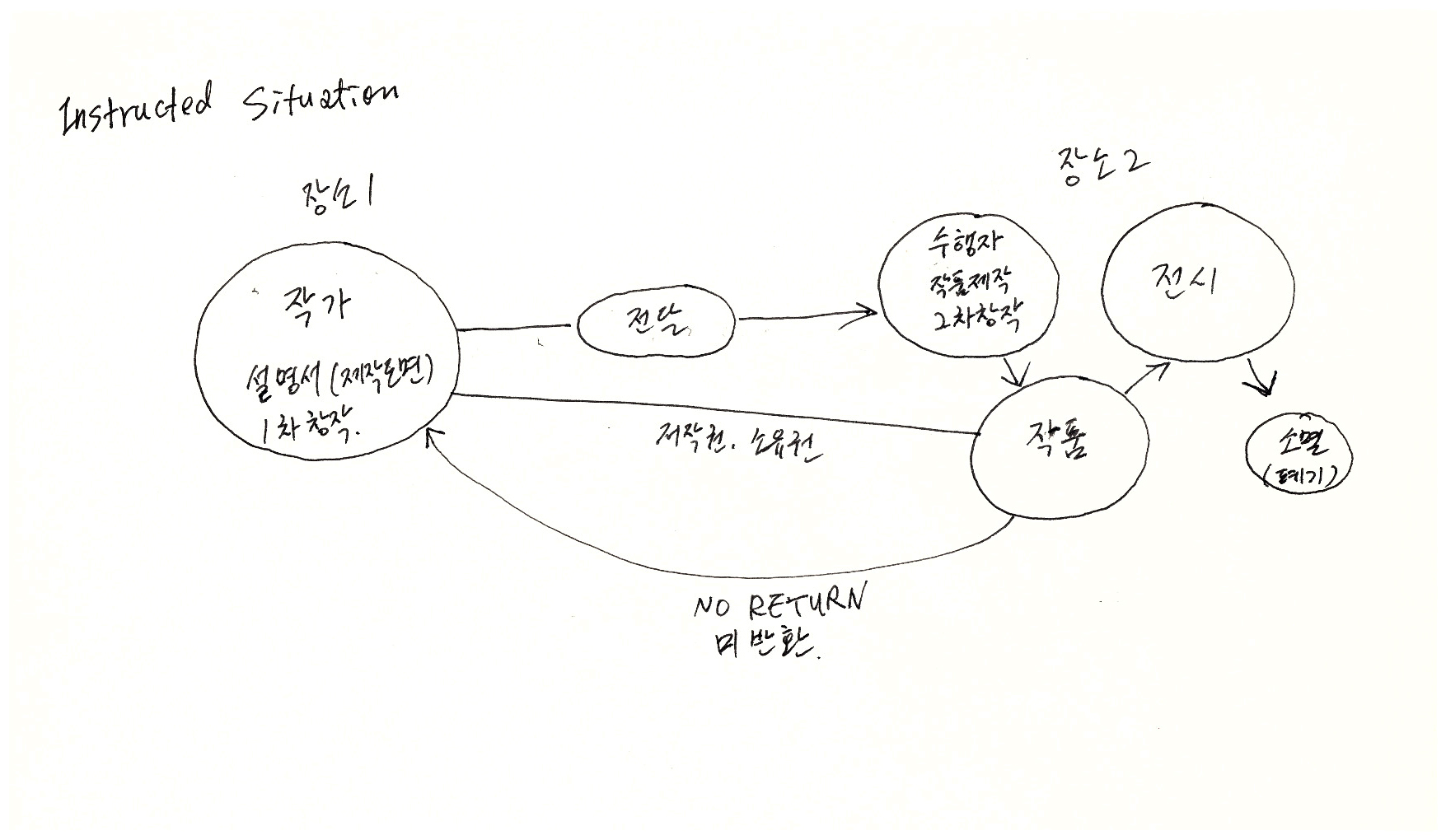

Instructed Situation, Constructed Situation

Artist Tino Sehgal doesn’t appear in his performances called “constructed situations”; he gets other people to participate and perform. Even if the same pieces were to take place at another time in another venue, they would be performed identically by another group of participants. The reason this is possible, as in theater, is for the instructions provided to the performers; Tino Sehgal informs over the phone or via email what the performers need to do. Through these “instructions,” all manner of “situations” could now be reenacted. So, did Tino Sehgal invent this form of expression? While he uses the term “constructed situations” to define his performances, we may usefully apply the term to any ambiguous works that are tricky to place under art. For example, consider Jannis Kounellis, an artist associated with Arte Povera. His Untitled (Cavalli) from 1967 featured 12 horses eating hay in a gallery. The reason we find this piece so provocative is probably for his ambitious demand that we accept living animals as a work of art. The unexpectedness of encountering a dozen big horses in a gallery located in a city, the smell of livestock and hay permeating the space... How can we define a situation like this as a work of art? If we do call it art, then how can a museum collect living horses? For the purpose of collection, would photo documentation and a note of instructions stand in for the real thing? How can instructions represent living horses, though? Here, we may switch our perspective and view this work as an “instructed situation” rather than an installation or a happening. This way, recreating the work elsewhere at another time would pose no problem; as long as the instructions are followed, the 12 horses could be viewed at other times in Seoul, New Delhi, or Copenhagen. And these recreations could even bear the same title. Indeed, Untitled (Cavalli) was recreated at Art Cologne in 2006.

![]()

Jannis Kounellis, Untitled (Cavalli), 1967, 12 horses, installation view at Galleria L’attico, Rome, 1969

![]()

Jannis Kounellis, Untitled (12 Horses), 2015.

A NYC art gallery displayed 12 live horses for four days

On the possibility of “instructions” reviving artworks, a good case in point would be works by Félix González-Torres, who would install everyday objects like candies, lightbulbs, or stacks of paper. The artist pointed out that those installations could very well be completed without his appearing at the exhibition location. The person in charge of actual installing on-site could arrange the candies or lightbulbs in a manner they saw fit, and the result became González-Torres’s work. As long as the artist’s brief instructions were followed, say, “Have the lightbulbs hang down heavily from the ceiling” or “Stretch them out on the floor,” the lightbulbs could be purchased from whatever region the exhibition was being held in. As such, the artist’s instructions acted as the singular arbiter determining whether or not a given installation was his work. This practice might be dismaying to those who set great store by the auteur theory. But it is true that hanging strings of lightbulbs or making mounds of candies doesn’t really require the keen eye and delicate touch of an artist; anybody can manage that without expert help. Therefore, whenever González-Torres’s work is installed in a new place, the person tasked with overseeing the installation, while abiding by the artist’s instructions, can shape the work in a unique site-specific fashion, thereby creating something wholly new. In other words, while originating from the identical instructions, recreations of his work can be imbued with different interpretations in different locations, which makes his work a kind of shape-shifting monster. Of course, all his independent works are exhibited in his name González-Torres. His installations, thus, operate by “instruction,” not “situation.”

![]()

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled (For Stockholm), 2011, MMK, Frankfurt

![]()

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled (For Stockholm), 1992-1993

Stockholm Kontshall, Stockholm

As these instances show, a lot of things have gained the potential to be works of art. Yet, for those who think highly of the authority and presence of the artist, works like González-Torres’s might be hard to accept as art, since anyone with the artist’s permission to purchase the material and install per his instructions could more or less identically recreate his work. Let’s suppose a café owner who is familiar with González-Torres’s work recreated his piece in their café. People who respect the authority of artwork might get very upset by this installation. This certainly is an issue, although, of course, works with a certificate of authenticity issued by the artist and those without would be very different things.

![]()

<Instructed Situation>-Diagram of the relationship between production, distribution, and exhibition of art works

![]() Diagram of the relationship between production, distribution, and exhibition of art works

Diagram of the relationship between production, distribution, and exhibition of art works

González-Torres’s work is not just for viewing; viewers are invited to take a candy or a poster from the installed mass and the material constituting the work disappears. Thus, his work achieves completion by public participation. When it comes to collection, however, if a museum scatters a bunch of candies and stacks posters on the floor per “instructions” and awaits viewers, can we say that his work has been recreated? Have we reached a consensus to accept this form of exhibition as an appropriate recreation of his work, because, unlike other performance art pieces, his work defies representation by photographic documentation?

The Hirshhorn Museum purchased Tino Sehgal’s This You (2006) without a contract, without photos or any other documentation pertaining to the work. The transaction was fulfilled by an oral contract only, in which the notary representing Tino Sehgal explained the artist’s terms to the buyer. This means that their contract and transaction were conducted solely through conversation. Thus occurred the very first case of an artwork changing hands without any paperwork. This was also the first instance in which a purely immaterial work—one that is not a video, a photo, or a printed text—was sold. While this was a milestone event that attested to conceptual expansion, what it expanded more than artistic freedom was the scope of commercial transactions by galleries. Of course, the majority of museums still require documentation, but the possibility that a performance could be purchased “as is,” with not even a video record standing in for it, laid the foundation upon which action-centered Live Art has come to occupy a segment of the art market, a vigorous one too.

In 2010, the Pompidou Center ran into a bit of a predicament too when it tried to purchase Tino Sehgal’s This Situation. An artwork description sheet was typically required in the transaction process, and yet, per Sehgal’s principles, such a thing was not admissible. Although a brief explanation couldn’t be helped, other than that, the news of the acquisition could only be transmitted through word of mouth. Even if the Center wanted to introduce the work, without any photos, that was quite the impossible task.

Tino Sehgal had started his project with an emphasis not on the performance itself but on the idea “unpurchasability” and getting the public to understand it. Needless to say, purchasing the actions comprising This Situation was impossible. And yet, Sehgal stated, “In order to complete this work, in order to rid it of incompleteness, in order for this work to be realized, the museum will have to buy that which isn’t any thing.”

We wonder about the relationship between Sehgal and the performers. No one thinks that he would have just let the performers be. But with nothing known about what tasks or instructions he gave them, it’s your-guess-is-as-good-as-mine. None of the performers’ names could be found in what little information the public had available, and even the critics knew no better, who only thought that they were professional actors. With such secrecy shrouding the work, there was no way to know whether the performance was spontaneous or scripted. One could pick up some cultural reflections from the performers’ brief conversations, but couldn’t tell if they were rehearsed or improvised. Judging from this, the performers seemed to be intellectuals, professors, perhaps experts in human sciences, rather than actors. It has been said that despite Sehgal’s rather stringent terms and demands, the performers were content with a small payment. Honor might have been the most compelling compensation of all.

That Sehgal’s work became part of a museum’s collections means that, unless it was a donation, the work had been turned into an asset. The performers in the work included two types: those whose participation was voluntary and nonprofit and those who acknowledged, through monetary compensation, that their performance belonged to the artist’s work. Even if they performed for a living, could they really accept that their performance wholly came under the artist’s intellectual property rights? That a museum acquired Sehgal’s work implies that they purchased the performers’ actions, which means in the event that the work is recreated, it can be performed by any group of people appointed by the museum. However, if we are to recognize that the performers in Sehgal’s work are a crucial element for their performance and for their very being, then selling his work couldn’t be so free from ethical considerations. We have seen numerous instances like this in the art world already. And it seems that we need dialogue on whether it is fair that a performer’s expertise and actions of spontaneity should be subsumed under the intellectual property rights of the artist who planned the performance, and whether it is fair that their performance, so swiftly as a matter of course, gets lost in the authority of the artist. We need this dialogue because ethics are not proclaimed but discussed, are not a priori truths but learned practices.

Tino Sehgal sold his work to a museum. If the museum wishes to exhibit his work to the public, performers will be assembled in a designated place and they will perform according to the artist’s instructions. Per his principles, no records of any kind, neither video nor printed matter, will be made available to us. So, if we want to see his work, we will have to visit the museum that owns the work at the designated performance time. Is this an appropriate practice of the idea that artworks should serve as public goods? Must we physically take ourselves to the work in order to respect the artist’s principles? Then, being a resident of Seoul, do I have to fly to Berlin to see his work? Denying approachability as public goods while claiming that doing so is a form of individual expression, hence an acceptable practice—is the wielding of such artistic authority a convention we can agree to?

Question 5

Platform for the reenactment of reality

Neither reality, theatre nor performance

In the 2000s, we saw a spate of performance art pieces featuring ordinary people. Works of “relational art,” as termed by Nicolas Bourriaud, cropped up around the world, highlighting the concept of “globalization.” Thai artists such as Surasi Kusolwong, Navin Rawanchaikul, and Rirkrit Tiravanija foregrounded the concept of “welcome,” offering everyone a chance to casually participate in their work. Other artists, including Félix González-Torres, Pierre Huyghe, Philippe Parreno, Jens Haaning, and Superflex, completed their work by enlisting collaboration or participation of numerous people. The people who appeared in relational art pieces were not viewers but the public, and therein lies the significance of these works: that they reached out to not “audiences” foremost, but “people.” As such, relational art was an attempt at renegotiating the relationship between artwork and the public.

Rirkrit Tiravanija’s work in the 90s was considered participatory art rather than performance art as audiences were naturally brought into his work. But since they weren’t the central figures either, it must have been tricky to name his work. Since then, Tiravanija’s work has come to be known as relational art rather than participatory art and the artist is considered its representative practitioner. The significance of his work, art-historically, is that it made artwork out of people. By bringing people into his work, it is not that Tiravanija objectified them; rather, he let them be themselves. In order to achieve this, Tiravanija adopted spaces commonly seen around us. But unlike Ilya Kabakov who replicated everyday spaces at the exhibition site, Tiravanija set up temporary spaces “for people.” People made themselves protagonists of those makeshift spaces, performing actions as visitors/users would. The spaces didn’t exactly look like the real ones established in our society—restaurants, studios, lounges, libraries—only suggestive of them; the point was for the spaces to function as the real ones, not to look identical to them. In other words, they weren’t reproductions of certain spaces but platforms on which people could do things. As such, the spaces themselves weren’t very important in Tiravanija’s work; the work was the people who were there being themselves, the suggestion thereof being: ultimately, life is art.

Then, how would a museum collect an artwork that is essentially people showing up and doing things? How could a gallery sell such a work? No gallery bought it, of course. Even a museum couldn’t collect the work, not the exact one. Presenting a one-time-only situation, Tiravanija had dismantled the materiality of art, and as such, it was pointless to expect a reproduction. Take Untitled (Free), an exhibition in which Tiravanija served pad thai to the gallery’s visitors. How can this be recreated? When MoMA acquired the work, they collected objects like the kitchenware Tiravanija used to cook. But those were only mementos to commemorate his lengthy performance, not something representative of his work. His work may be collected in the manner that Abramović’s performance was collected. But unlike Abramović’s piece in which the artist herself starred and performed, Tiravanija’s work featured as its central cast the numerous, daily-varying people who visited the site. So how can these two works be comparable? How can some photos of the numerous people populating the situation truly represent the work? That it may be recreated à la “instructed situation” mentioned earlier also doesn’t hold water. While it is possible to recreate the sequence of what occurred in the original situation similarly, doing so identically is impossible. So there can’t be a second or third work that can replace the work. In other words, the original exists, but nothing can represent it, so the original can only ever remain the one and only, one-time-only work. A second dining hall may pop up, but it will only be a situation that keeps on imitating the first. And in the end, what we will have is this forced statement: every time it is not the same as the original, but it is a new original. As such, “art-that-is-people” is a situation of contradiction where we claim that the original is that which is nonexistent, visually.

![]()

Diagram of Rirkrit Tiravanija’s work

Considering all this, can we call Tiravanija’s work art? Isn’t it, rather, something that doesn’t have a name in our current conceptual system? Something between theater and reality, between politics and entertainment, between symposium and festival?

Question 6

Situation of In-betweenness

In 2012, Gimhongsok presented an experimental piece of performance art at the National Museum of Contemporary Art. In this exhibition, he constructed three rooms of identical size and installed an identical set of artworks of various mediums, from painting to sculpture, in each of the rooms. Well, they weren’t identical, only very similar; the point of the exhibition was not that the installations were precise replicas but that the museum’s visitors had the experience of touring the three rooms consecutively. The rooms were only a backdrop, however; it was the texts and people in them that were the main component of the work. And “people” here doesn’t refer to visitors, but docents. Gimhongsok thought that in the process of making art and exhibiting it, people whom the artist actually got to meet weren’t the public; rather, the artist’s direct interactions were with curators, critics, actors, docents, assistants, museum staff, and temporary workers. This thought inspired Gimhongsok’s four-part performance art series entitled People Objective, of which the exhibition featuring docents was the second part.

In the three rooms named “Room of Labor,” “Room of Manner,” and “Room of Metaphor,” Gimhongsok installed identical artworks and had docents come in and provide commentary on them. To highlight that many different interpretations and meanings could be derived from the same work, he actually prepared three different texts. Each room had a docent assigned and they shared their knowledge to the room’s visitors. This work joined the museum’s collections in 2016. Once the acquisition was decided, as Gimhongsok and the museum’s Conservation Department staff were having a discussion, the artist recognized a big difference in perspective between the two of them: the museum’ s reason for collecting the work and what the artist thought to be his work’s main component weren’t aligned. Gimhongsok explained that the main object of collection should be the docents. But, of course, as people can’t be collected, he said that his work could be represented by the texts that were provided to the docents. On the other hand, the museum wanted to collect the paintings and sculptures that had furnished the rooms. According to their plan, in future exhibitions, they could show one piece of the paintings and one piece of the sculptures. But this plan was dashed by Gimhongsok’s explanation. The docents he enlisted for his work were people with a very specific objective behind their actions. Unlike the public, the “anonymous multitude,” in Tiravanija’s work, these docents were invitees and “active participants,” so the implications of recreation were different for Gimhongsok’s work than for Tiravanija’s. While the appearance of another “anonymous multitude” poses no issue, having a different set of “active participants” would substantially change the work; that is, it would turn into a different work. Gimhongsok mentioned that his performance series illustrated the “space between” artwork and people.

![]()

![]()

![]()

gimhongsok, People Objective – Wrong Interpretations, 2012.

Installation view at National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, 2012

36 volunteer docents

Performance held 8 times a day (between 10am-6pm), 6 days a week

August 31st – November 11th, 2012

![]()

![]()

![]()

gimhongsok, People Objective—Wrong Interpretations, 2012.

Installation view at National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, 2012.

<Room of Labor>, <Room of Manner>, <Room of Metaphor>

In 2013, Gimhongsok invited three art theorists to Plateau Museum to each present a lecture on his work. The lectures took place on a designed date during the exhibition period. Gimhongsok called this an “indefinable performance.” Each theorist did perform a lecture, but it was hard to call that performance art. A few complications lie here, though. Even if this performance were to end up an irreproducible, one-off event, you could call it a work of art if the lectures were taken as a kind of artistic expression. To recreate this work at another time in another place, the same lecturers would have to show up again and deliver the same lectures, the likelihood of which is minimal if not nonexistent. The second issue is that the contents of the lectures came from the three lecturers themselves, meaning that the contents are their intellectual proper ty. So calling their lectures Gimhongsok’s performance would be treading on dangerous ground. Even if they received an honorarium from the artist for their critical texts and lectures, these can’t become Gimhongsok’s property. If the two parties conspire and the lecturers hand over the copyrights on their texts to Gimhongsok, they may be legally in the clear, but the texts are still the lecturers’.

![]()

![]()

![]()

gimhongsok, People Objective – Good Critique, Bad Critique, Strange Critique, 2013.

Installation view at Plateau, Seoul in 2013.

three critics, texts and lectures

Through this performance Gimhongsok sought to shed light on that ambiguous space which you might call a “gap” or “void.” If a museum were to collect this work, what type of collection would that be? Could photos or videos stand in for the work? Would the museum ask the critics to give up or sell their copyrights? This shouldn’t be just about navigating ethical hurdles; more fundamentally, if the main issue entailed here is the act of converting someone’s intellectual property into another’s possession, isn’t the very idea of trying to give a tangible or visible form to the immaterial problematic?

Then, could other mediums represent Gimhongsok’s performance? Within the museum’s collections management system, should the video record of this work filed under “single-channel video” or “new media”?

When it comes to performances involving different times, locations, and performers, should we let those works remain as irreproducible, one-time-only events? Or, could they be reproduced?■

Separation of areas for the role of an artist

Question 1

Performance utilizing photography and video

Let’s first look at Marina Abramović’s performance art piece from the 80s. This work was represented by videos and photos. The idea that a performance could be collected did not obtain at the time, so material mediums such as video and photography stood in for the original work. For this reason, even though Abramović designated Rhythm 0 as a work of performance art, the museums that bought the work classified it otherwise. The collection record at the Guggenheim reads that while the tendency of Rhythm 0 is performance, its collection type is photography. Similarly, Tate labels the work as “72 objects and a slide projector with slides documenting the performance.”

GUGGENHEIM COLLECTION

Marina Abramović

Rhythm 0

ARTIST

Marina Abramović

b. 1946, Belgrade, Yugoslavia

TITLE

Rhythm 0

DATE

1975 (published 1994)

MEDIUM

Gelatin silver print with inset letterpress panel

DIMENSIONS

frame (photograph): 38 5/8 x 39 5/8 x 1 inches (98.1 x 100.7 x 2.5 cm); frame (text): 10 3/16 x 7 3/16 x 1 inches (25.9 x 18.3 x 2.5 cm)

CREDIT LINE

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Gift, Willem Peppler, 1998

COPYRIGHT

© 2018 Marina Abramović, courtesy of Sean Kelly Gallery/(ARS), New York

ARTWORK TYPE

Photography

MOVEMENT

Performance

Tate Collections

ARTIST Marina Abramovic born 1946

MEDIUM Table with 72 objects and slide projector with slides of performance and text

DIMENSIONS Overall display dimensions variable

COLLECTION Tate

ACQUISITION Presented by the Tate Americas Foundation. 2017

A performance can be collected in the form of videos and photos; granted, we cannot say that those are the original. They may represent the original, but that is a woefully inadequate representation. And this is not an issue of technology but one that is fundamentally irresolvable. Thus, artists have brought into art’s realm what cannot be preserved as art and obtained consent from all parties involved.

Museums began to collect performances as videos and photos and labeled them as such even when the artist specified their work to be performance art. Then, how do we differentiate between an artist who uses photography merely as a tool for documenting his/her performance and another artist who presents such documentation as a work of art in and of itself? Their performances are collected as photos—that goes for both artists. But if one artist claims that their original work is performance art and the other claims that, even so, the ultimate medium is photography, then should the collection records reflect the respective artists’ claims? I do think that both claims are legitimate. The medium of an artwork is determined by what the artist chose as their medium of expression. The reason why Abramović’s Rhythm 0 can’t be called photography is that Abramović decided that the work was performance art, not photography. Then why did she allow photos to serve as a proxy for her performance? And who decided this conversion of mediums anyway? Was it a shrewd new way of art collecting devised by then-powerful art museums? And has that since become a convention?

To sum up the questions: Are the photos at the Guggenheim documenting Abramović’s performance the original work? Or are they an archive collected for academic/educational purposes?

Question 2

Ethical Politics

Next, I would like to look at Shirin Neshat’s work. Neshat’s work arises from indirect criticism of social/political inequality and gender discrimination prevalent in Islamic societies and the absurdities of Iranian culture. In her photos and videos frequently appear Iranian women draped in chadors; Neshat uses them as material in her attempt to criticize the perceptive discrimination historically perpetrated against women. As we look at the Iranian people featured in Neshat’s work, immediately we get to wondering about a few things: Did those women in chadors participate because they met the desired conditions for their incorporation into Neshat’s art? Were they active participants who understood Neshat’s intents? Have they seen change in their circumstances since they appeared in her work? Do they know that Neshat’s work has gained international recognition? That the artist has earned great frame?

Despite Neshat’s political correctness, the question remains/ whether the people and their milieu adopted as material for promoting the very correctness truly function/ as independent subjects with agency. A distinction needs to be made between “those who participate in the production of an artwork” and “those who participate in an artwork.” The people who appear in Neshat’s work are not the crew hired for production but the cast. As the copyright on the work belongs to Neshat, the relationship between the artist and the cast could be formulated as an economic one by means of a wage or honorarium. However, in the event that the work achieves great acclaim, all the glory goes to the artist while the people who appeared in it see no change in their position, resulting in an unfair, hierarchical situation. The artist who created the work owns the copyright to it—legally speaking, there is nothing problematic about that statement. And yet it is troubling, ethically, and that is because the artist’s intellectual property was created collaboratively, involving many people, and through that property the artist gets to occupy a positon of great prominence.

The copyright on a performance that was conceived by an artist but completed by other participants nonetheless belongs solely to the artist, for the reason that the idea came from the artist. Here, do we classify participants who are specialists in certain fields as “employees” or “volunteers”? It would be hard to say unless there is a clear agreement reached between the artist and the participants. If they are considered employees and their expertise is of high caliber, then simply paying them hourly wages wouldn’t be fair. Does the notion prevail that the products of professional research, such as documentary films or anthropological photo records, are superior to the people who are featured in those products?

Affective labor is work carried out by managing one’s emotions and is a form of labor that is intended to trigger and expand interpersonal communication. Most of the performers appearing in Tino Sehgal’s work are professional dancers or ones with comparable skill. Besides demonstrating work ethic traits such as solidarity and teamwork, these performers as affective laborers function to expand human relationships, and as such, their labor is melded in their performances. Just as human actions could be instrumental, instrumental actions too have human aspects. Isn’t a major task of performance art bringing these human aspects to the forefront?

For videos and films featuring people, including documentaries, is it fair to grant the sole copyright ownership to the artist even when there were others involved who carried out affective labor? Legality aside, that is.

Question 3

Division of copyright

A few complications arise when a piece of performance art is performed not by the artist but by other participants. They could be ordinary people or specialists in specific fields. They may participate as collaborators or as temporary workers. Or they may be classified as volunteers and paid an honorarium for skills they exhibit. In some cases, instead of an honorarium, the payment could be made as a wage. Performing participants are not assistants or day laborers whose contributions have a material basis; rather, they provide affective labor through their bodily appearance and actions. If a performance like this becomes an object of commercial transactions through galleries, can we call it “merchandise”? Given that people can’t be merchandise, should we then consider the video documentation of the performance merchandise? Does the video have value as merchandise? How can performance art function as merchandise?

Artworks are at once public goods and merchandise: since when did we have this dual designation and through what process was that established? Can the concept of “public” be applied to art?

Question 4

Instructed Situation, Constructed Situation

Artist Tino Sehgal doesn’t appear in his performances called “constructed situations”; he gets other people to participate and perform. Even if the same pieces were to take place at another time in another venue, they would be performed identically by another group of participants. The reason this is possible, as in theater, is for the instructions provided to the performers; Tino Sehgal informs over the phone or via email what the performers need to do. Through these “instructions,” all manner of “situations” could now be reenacted. So, did Tino Sehgal invent this form of expression? While he uses the term “constructed situations” to define his performances, we may usefully apply the term to any ambiguous works that are tricky to place under art. For example, consider Jannis Kounellis, an artist associated with Arte Povera. His Untitled (Cavalli) from 1967 featured 12 horses eating hay in a gallery. The reason we find this piece so provocative is probably for his ambitious demand that we accept living animals as a work of art. The unexpectedness of encountering a dozen big horses in a gallery located in a city, the smell of livestock and hay permeating the space... How can we define a situation like this as a work of art? If we do call it art, then how can a museum collect living horses? For the purpose of collection, would photo documentation and a note of instructions stand in for the real thing? How can instructions represent living horses, though? Here, we may switch our perspective and view this work as an “instructed situation” rather than an installation or a happening. This way, recreating the work elsewhere at another time would pose no problem; as long as the instructions are followed, the 12 horses could be viewed at other times in Seoul, New Delhi, or Copenhagen. And these recreations could even bear the same title. Indeed, Untitled (Cavalli) was recreated at Art Cologne in 2006.

Jannis Kounellis, Untitled (Cavalli), 1967, 12 horses, installation view at Galleria L’attico, Rome, 1969

Jannis Kounellis, Untitled (12 Horses), 2015.

A NYC art gallery displayed 12 live horses for four days

On the possibility of “instructions” reviving artworks, a good case in point would be works by Félix González-Torres, who would install everyday objects like candies, lightbulbs, or stacks of paper. The artist pointed out that those installations could very well be completed without his appearing at the exhibition location. The person in charge of actual installing on-site could arrange the candies or lightbulbs in a manner they saw fit, and the result became González-Torres’s work. As long as the artist’s brief instructions were followed, say, “Have the lightbulbs hang down heavily from the ceiling” or “Stretch them out on the floor,” the lightbulbs could be purchased from whatever region the exhibition was being held in. As such, the artist’s instructions acted as the singular arbiter determining whether or not a given installation was his work. This practice might be dismaying to those who set great store by the auteur theory. But it is true that hanging strings of lightbulbs or making mounds of candies doesn’t really require the keen eye and delicate touch of an artist; anybody can manage that without expert help. Therefore, whenever González-Torres’s work is installed in a new place, the person tasked with overseeing the installation, while abiding by the artist’s instructions, can shape the work in a unique site-specific fashion, thereby creating something wholly new. In other words, while originating from the identical instructions, recreations of his work can be imbued with different interpretations in different locations, which makes his work a kind of shape-shifting monster. Of course, all his independent works are exhibited in his name González-Torres. His installations, thus, operate by “instruction,” not “situation.”

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled (For Stockholm), 2011, MMK, Frankfurt

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled (For Stockholm), 1992-1993

Stockholm Kontshall, Stockholm

As these instances show, a lot of things have gained the potential to be works of art. Yet, for those who think highly of the authority and presence of the artist, works like González-Torres’s might be hard to accept as art, since anyone with the artist’s permission to purchase the material and install per his instructions could more or less identically recreate his work. Let’s suppose a café owner who is familiar with González-Torres’s work recreated his piece in their café. People who respect the authority of artwork might get very upset by this installation. This certainly is an issue, although, of course, works with a certificate of authenticity issued by the artist and those without would be very different things.

<Instructed Situation>-Diagram of the relationship between production, distribution, and exhibition of art works

Diagram of the relationship between production, distribution, and exhibition of art works

Diagram of the relationship between production, distribution, and exhibition of art worksGonzález-Torres’s work is not just for viewing; viewers are invited to take a candy or a poster from the installed mass and the material constituting the work disappears. Thus, his work achieves completion by public participation. When it comes to collection, however, if a museum scatters a bunch of candies and stacks posters on the floor per “instructions” and awaits viewers, can we say that his work has been recreated? Have we reached a consensus to accept this form of exhibition as an appropriate recreation of his work, because, unlike other performance art pieces, his work defies representation by photographic documentation?

***

The Hirshhorn Museum purchased Tino Sehgal’s This You (2006) without a contract, without photos or any other documentation pertaining to the work. The transaction was fulfilled by an oral contract only, in which the notary representing Tino Sehgal explained the artist’s terms to the buyer. This means that their contract and transaction were conducted solely through conversation. Thus occurred the very first case of an artwork changing hands without any paperwork. This was also the first instance in which a purely immaterial work—one that is not a video, a photo, or a printed text—was sold. While this was a milestone event that attested to conceptual expansion, what it expanded more than artistic freedom was the scope of commercial transactions by galleries. Of course, the majority of museums still require documentation, but the possibility that a performance could be purchased “as is,” with not even a video record standing in for it, laid the foundation upon which action-centered Live Art has come to occupy a segment of the art market, a vigorous one too.

In 2010, the Pompidou Center ran into a bit of a predicament too when it tried to purchase Tino Sehgal’s This Situation. An artwork description sheet was typically required in the transaction process, and yet, per Sehgal’s principles, such a thing was not admissible. Although a brief explanation couldn’t be helped, other than that, the news of the acquisition could only be transmitted through word of mouth. Even if the Center wanted to introduce the work, without any photos, that was quite the impossible task.

Tino Sehgal had started his project with an emphasis not on the performance itself but on the idea “unpurchasability” and getting the public to understand it. Needless to say, purchasing the actions comprising This Situation was impossible. And yet, Sehgal stated, “In order to complete this work, in order to rid it of incompleteness, in order for this work to be realized, the museum will have to buy that which isn’t any thing.”

We wonder about the relationship between Sehgal and the performers. No one thinks that he would have just let the performers be. But with nothing known about what tasks or instructions he gave them, it’s your-guess-is-as-good-as-mine. None of the performers’ names could be found in what little information the public had available, and even the critics knew no better, who only thought that they were professional actors. With such secrecy shrouding the work, there was no way to know whether the performance was spontaneous or scripted. One could pick up some cultural reflections from the performers’ brief conversations, but couldn’t tell if they were rehearsed or improvised. Judging from this, the performers seemed to be intellectuals, professors, perhaps experts in human sciences, rather than actors. It has been said that despite Sehgal’s rather stringent terms and demands, the performers were content with a small payment. Honor might have been the most compelling compensation of all.

That Sehgal’s work became part of a museum’s collections means that, unless it was a donation, the work had been turned into an asset. The performers in the work included two types: those whose participation was voluntary and nonprofit and those who acknowledged, through monetary compensation, that their performance belonged to the artist’s work. Even if they performed for a living, could they really accept that their performance wholly came under the artist’s intellectual property rights? That a museum acquired Sehgal’s work implies that they purchased the performers’ actions, which means in the event that the work is recreated, it can be performed by any group of people appointed by the museum. However, if we are to recognize that the performers in Sehgal’s work are a crucial element for their performance and for their very being, then selling his work couldn’t be so free from ethical considerations. We have seen numerous instances like this in the art world already. And it seems that we need dialogue on whether it is fair that a performer’s expertise and actions of spontaneity should be subsumed under the intellectual property rights of the artist who planned the performance, and whether it is fair that their performance, so swiftly as a matter of course, gets lost in the authority of the artist. We need this dialogue because ethics are not proclaimed but discussed, are not a priori truths but learned practices.

Tino Sehgal sold his work to a museum. If the museum wishes to exhibit his work to the public, performers will be assembled in a designated place and they will perform according to the artist’s instructions. Per his principles, no records of any kind, neither video nor printed matter, will be made available to us. So, if we want to see his work, we will have to visit the museum that owns the work at the designated performance time. Is this an appropriate practice of the idea that artworks should serve as public goods? Must we physically take ourselves to the work in order to respect the artist’s principles? Then, being a resident of Seoul, do I have to fly to Berlin to see his work? Denying approachability as public goods while claiming that doing so is a form of individual expression, hence an acceptable practice—is the wielding of such artistic authority a convention we can agree to?

Question 5

Platform for the reenactment of reality

Neither reality, theatre nor performance

In the 2000s, we saw a spate of performance art pieces featuring ordinary people. Works of “relational art,” as termed by Nicolas Bourriaud, cropped up around the world, highlighting the concept of “globalization.” Thai artists such as Surasi Kusolwong, Navin Rawanchaikul, and Rirkrit Tiravanija foregrounded the concept of “welcome,” offering everyone a chance to casually participate in their work. Other artists, including Félix González-Torres, Pierre Huyghe, Philippe Parreno, Jens Haaning, and Superflex, completed their work by enlisting collaboration or participation of numerous people. The people who appeared in relational art pieces were not viewers but the public, and therein lies the significance of these works: that they reached out to not “audiences” foremost, but “people.” As such, relational art was an attempt at renegotiating the relationship between artwork and the public.

Rirkrit Tiravanija’s work in the 90s was considered participatory art rather than performance art as audiences were naturally brought into his work. But since they weren’t the central figures either, it must have been tricky to name his work. Since then, Tiravanija’s work has come to be known as relational art rather than participatory art and the artist is considered its representative practitioner. The significance of his work, art-historically, is that it made artwork out of people. By bringing people into his work, it is not that Tiravanija objectified them; rather, he let them be themselves. In order to achieve this, Tiravanija adopted spaces commonly seen around us. But unlike Ilya Kabakov who replicated everyday spaces at the exhibition site, Tiravanija set up temporary spaces “for people.” People made themselves protagonists of those makeshift spaces, performing actions as visitors/users would. The spaces didn’t exactly look like the real ones established in our society—restaurants, studios, lounges, libraries—only suggestive of them; the point was for the spaces to function as the real ones, not to look identical to them. In other words, they weren’t reproductions of certain spaces but platforms on which people could do things. As such, the spaces themselves weren’t very important in Tiravanija’s work; the work was the people who were there being themselves, the suggestion thereof being: ultimately, life is art.

Then, how would a museum collect an artwork that is essentially people showing up and doing things? How could a gallery sell such a work? No gallery bought it, of course. Even a museum couldn’t collect the work, not the exact one. Presenting a one-time-only situation, Tiravanija had dismantled the materiality of art, and as such, it was pointless to expect a reproduction. Take Untitled (Free), an exhibition in which Tiravanija served pad thai to the gallery’s visitors. How can this be recreated? When MoMA acquired the work, they collected objects like the kitchenware Tiravanija used to cook. But those were only mementos to commemorate his lengthy performance, not something representative of his work. His work may be collected in the manner that Abramović’s performance was collected. But unlike Abramović’s piece in which the artist herself starred and performed, Tiravanija’s work featured as its central cast the numerous, daily-varying people who visited the site. So how can these two works be comparable? How can some photos of the numerous people populating the situation truly represent the work? That it may be recreated à la “instructed situation” mentioned earlier also doesn’t hold water. While it is possible to recreate the sequence of what occurred in the original situation similarly, doing so identically is impossible. So there can’t be a second or third work that can replace the work. In other words, the original exists, but nothing can represent it, so the original can only ever remain the one and only, one-time-only work. A second dining hall may pop up, but it will only be a situation that keeps on imitating the first. And in the end, what we will have is this forced statement: every time it is not the same as the original, but it is a new original. As such, “art-that-is-people” is a situation of contradiction where we claim that the original is that which is nonexistent, visually.

Diagram of Rirkrit Tiravanija’s work

Considering all this, can we call Tiravanija’s work art? Isn’t it, rather, something that doesn’t have a name in our current conceptual system? Something between theater and reality, between politics and entertainment, between symposium and festival?

Question 6

Situation of In-betweenness

In 2012, Gimhongsok presented an experimental piece of performance art at the National Museum of Contemporary Art. In this exhibition, he constructed three rooms of identical size and installed an identical set of artworks of various mediums, from painting to sculpture, in each of the rooms. Well, they weren’t identical, only very similar; the point of the exhibition was not that the installations were precise replicas but that the museum’s visitors had the experience of touring the three rooms consecutively. The rooms were only a backdrop, however; it was the texts and people in them that were the main component of the work. And “people” here doesn’t refer to visitors, but docents. Gimhongsok thought that in the process of making art and exhibiting it, people whom the artist actually got to meet weren’t the public; rather, the artist’s direct interactions were with curators, critics, actors, docents, assistants, museum staff, and temporary workers. This thought inspired Gimhongsok’s four-part performance art series entitled People Objective, of which the exhibition featuring docents was the second part.

In the three rooms named “Room of Labor,” “Room of Manner,” and “Room of Metaphor,” Gimhongsok installed identical artworks and had docents come in and provide commentary on them. To highlight that many different interpretations and meanings could be derived from the same work, he actually prepared three different texts. Each room had a docent assigned and they shared their knowledge to the room’s visitors. This work joined the museum’s collections in 2016. Once the acquisition was decided, as Gimhongsok and the museum’s Conservation Department staff were having a discussion, the artist recognized a big difference in perspective between the two of them: the museum’ s reason for collecting the work and what the artist thought to be his work’s main component weren’t aligned. Gimhongsok explained that the main object of collection should be the docents. But, of course, as people can’t be collected, he said that his work could be represented by the texts that were provided to the docents. On the other hand, the museum wanted to collect the paintings and sculptures that had furnished the rooms. According to their plan, in future exhibitions, they could show one piece of the paintings and one piece of the sculptures. But this plan was dashed by Gimhongsok’s explanation. The docents he enlisted for his work were people with a very specific objective behind their actions. Unlike the public, the “anonymous multitude,” in Tiravanija’s work, these docents were invitees and “active participants,” so the implications of recreation were different for Gimhongsok’s work than for Tiravanija’s. While the appearance of another “anonymous multitude” poses no issue, having a different set of “active participants” would substantially change the work; that is, it would turn into a different work. Gimhongsok mentioned that his performance series illustrated the “space between” artwork and people.

gimhongsok, People Objective – Wrong Interpretations, 2012.

Installation view at National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, 2012

36 volunteer docents

Performance held 8 times a day (between 10am-6pm), 6 days a week

August 31st – November 11th, 2012

gimhongsok, People Objective—Wrong Interpretations, 2012.

Installation view at National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, 2012.

<Room of Labor>, <Room of Manner>, <Room of Metaphor>

In 2013, Gimhongsok invited three art theorists to Plateau Museum to each present a lecture on his work. The lectures took place on a designed date during the exhibition period. Gimhongsok called this an “indefinable performance.” Each theorist did perform a lecture, but it was hard to call that performance art. A few complications lie here, though. Even if this performance were to end up an irreproducible, one-off event, you could call it a work of art if the lectures were taken as a kind of artistic expression. To recreate this work at another time in another place, the same lecturers would have to show up again and deliver the same lectures, the likelihood of which is minimal if not nonexistent. The second issue is that the contents of the lectures came from the three lecturers themselves, meaning that the contents are their intellectual proper ty. So calling their lectures Gimhongsok’s performance would be treading on dangerous ground. Even if they received an honorarium from the artist for their critical texts and lectures, these can’t become Gimhongsok’s property. If the two parties conspire and the lecturers hand over the copyrights on their texts to Gimhongsok, they may be legally in the clear, but the texts are still the lecturers’.

gimhongsok, People Objective – Good Critique, Bad Critique, Strange Critique, 2013.

Installation view at Plateau, Seoul in 2013.

three critics, texts and lectures

Through this performance Gimhongsok sought to shed light on that ambiguous space which you might call a “gap” or “void.” If a museum were to collect this work, what type of collection would that be? Could photos or videos stand in for the work? Would the museum ask the critics to give up or sell their copyrights? This shouldn’t be just about navigating ethical hurdles; more fundamentally, if the main issue entailed here is the act of converting someone’s intellectual property into another’s possession, isn’t the very idea of trying to give a tangible or visible form to the immaterial problematic?

Then, could other mediums represent Gimhongsok’s performance? Within the museum’s collections management system, should the video record of this work filed under “single-channel video” or “new media”?

When it comes to performances involving different times, locations, and performers, should we let those works remain as irreproducible, one-time-only events? Or, could they be reproduced?■

미술작품은 무엇을 하는가? 미술의 영역은 어디까지 인가? 미술작품의 주인은 누구인가, 그것을 만든 미술가인가? 우리는 미술가에게 무엇을 기대하는가?

모더니즘 이후 미술가들은 작품을 제작하여 완성한 것을 최종적 단계라고 보았다면, 미디어가 등장하고 국가 차원의 다양한 미술 행사가 생겨난 이래, 미술가들은 작품 생산 단계를 넘어 전시라는 영역까지 책임지게 되었다. 작품을 제작하여 발표한다는 것은 이 시대의 미술가의 소임으로는 부족해졌다. 전시와 카탈로그에 자신의 작품이 어떻게 출현해야 적당한지, 그러기 위해 작품을 사진으로 기록하고 어떤 방식으로 촬영해야 하는지에 대해 결정하기에 이르렀다. 작품이 아틀리에에서 제작되었다고 임무가 끝난 것이 아니라 전시공간을 분석하고 전시공간과 작품 간의 다양한 가능성을 연구하기 시작한 것이다. 나아가 상업화랑은 물론 미술관에서는 미술가에게 작품에 대한 정보를 요구하고 작품에 대한 설명, 나아가 인터뷰나 강연 등을 요청하기 때문에 미술가들은 작품에 대해 전문적 내용과 대중적 설명까지 준비하게 되었다. 카탈로그는 물론이고 인터넷 공간까지 미술가들은 자신의 작품에 대한 온갖 정보를 준비하고 제공해야 하는 역할마저 수행했던 것이다.

미술작품이 전시장에 나타나 대중들에게 공개된다는 것은 그 작품이 공공적(公共的) 사물이라는 것을 의미한다. 작품은 개인에 의해 만들어 진 개인의 사유물이지만 이 시대의 작품은 공공(public)의 사명을 함께 갖는 것이다. 아틀리에에서 있는 작품은 작가 개인의 사유물이지만 전시장으로 이동하게 되면 문화적 자산으로 변하는 것이다.

이제 우리는 미술작품에 대해 질문할 것이 많다는 것을 알게 되었다. 예를 들면, 미술작품은 미술관의 선택을 받으면 공공재가 되는 것인가, 미술관의 전시는 공리적인 목적을 갖고 있는가, 아니면 적어도 공준(公準)인가?

![]()

도표 0. 미술가의 역할에 대한 영역 구분

질문 1.

사진과 비디오에 의한 퍼포먼스 Performance utilizing photography and video

마리나 아브라모비치(Marina Abramovic)의 80년대 퍼포먼스 작품은 비디오와 사진이라는 매체가 원본을 대표했다. 퍼포먼스가 작품이었지만 당시 인식으로는 행위를 소장할 수 없었기 때문에 사진이나 동영상이 작품을 대신했던 것이다. 이런 이유로 그녀의 퍼포먼스 작품 <Rhythm 0>의 경우, 그녀는 자신의 작품을 퍼포먼스라고 기록했으나, 그녀의 작품을 구입한 미술관은 다른 매체로 기록하고 있다. 구겐하임 미술관의 소장 기록을 보면 <Rhythm 0>는 퍼포먼스이나 소장상태는 사진이라고 적시되어 있고, 테이트(Tate)에서는 72가지의 오브제와 슬라이드 프로젝션용 사진필름으로 소장했다.

![]()

GUGGENHEIM COLLECTION

Marina Abramović

Rhythm 0

ARTIST

Marina Abramović

b. 1946, Belgrade, Yugoslavia

TITLE

Rhythm 0

DATE

1975 (published 1994)

MEDIUM

Gelatin silver print with inset letterpress panel

DIMENSIONS

frame (photograph): 38 5/8 x 39 5/8 x 1 inches (98.1 x 100.7 x 2.5 cm); frame (text): 10 3/16 x 7 3/16 x 1 inches (25.9 x 18.3 x 2.5 cm)

CREDIT LINE

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Gift, Willem Peppler, 1998

COPYRIGHT

© 2018 Marina Abramović, courtesy of Sean Kelly Gallery/(ARS), New York

ARTWORK TYPE

Photography

MOVEMENT

Performance

![]()

Tate Collections

ARTIST Marina Abramovic born 1946

MEDIUM Table with 72 objects and slide projector with slides of performance and text

DIMENSIONS Overall display dimensions variable

COLLECTION Tate

ACQUISITION Presented by the Tate Americas Foundation. 2017

다른 예로 1972년에 행해진 비토 아콘시(Vito Acconci)의 퍼포먼스 작품 <Seedbed>는 행위, 장소, 상황이 작품의 주된 주체였지만, 비디오와 사진으로 기록되었고 두 가지 기록물이 미술관에 소장되었다.

![]() Tate Collections

Tate Collections

Artwork title: Seedbed

Artist name: Vito Acconci

Part of: Sonnabend Show Jan 72: Archives

Medium: 3 works on paper, photographs, ink and printed papers

Dimensions: Support: 851 × 1233 mm / Support: 663 × 1295 mm / Support: 772 × 1544 mm

Acquisition: Presented by the Billstone Foundation 2009

MOMA Collections

Artwork title: Seedbed

Artist name: Vito Acconci

Medium: Super 8 film transferred to video (color, silent)

Duration: 10 min.

Credit: Gift of the Julia Stoschek Foundation, Düsseldorf and Committee on Media Funds

Object number: 191.2007

Copyright: © 2020 Vito Acconci. Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

Department: Media and Performance

사진과 비디오가 미술의 독립적 매체로 인정되었음에도 퍼포먼스는 매체적 한계로 인해 보존이 어려웠다. 퍼포먼스는 사진과 비디오에 빚을 졌고, 사진과 비디오는 퍼포먼스를 대신하는 매체로 기능했다. 그러나 사진과 비디오는 퍼포먼스라는 매체의 본질적인 것을 다시 재현할 수 없다는 점에서 원본이라고 할 수는 없다. 원본을 대표한다는 점에서도 빈약하기 그지없다. 이것은 테크놀로지의 문제가 아니라 근본적으로 해결할 수 없는 것이다. 결국 미술가들은 미술로써 보존할 수 없는 것을 미술이라는 영역에 포함시켰고, 관련된 모든 이들에게 합의를 받아 낸 셈이다.

이렇듯 퍼포먼스는 비디오나 사진으로 대체되어 그것이 미술관에 소장되었다. 미술가가 자신의 퍼포먼스 작품을 퍼포먼스라고 명기했더라도 소장(콜렉션) 상태는 비디오나 사진으로 대체되었다. 그렇다면 자신의 퍼포먼스를 사진으로 기록하여 사진 작품으로 발표하는 작가와 어떻게 구별해야 할까? 두 작품 모두 사진으로 소장되었지만 작가가 그 작품의 원형은 퍼포먼스라고 명기하면 사진임에도 불구하고 퍼포먼스라고 기록되고, 작품이 퍼포먼스이지만 사진 작품이라고 주장하면 사진이 되는 걸까? 맞다. 작가가 작품의 표현 매체(medium)를 결정한대로 작품의 매체가 결정되는 것이다. 위에 언급한바와 같이 아브라모비치의 <Rhythm 0>는 사진 작품이라고 할 수 없는 이유는 작가인 아브라모비치가 자신의 작품을 사진이 아닌 퍼포먼스라고 결정했기 때문이다. 그런데 아브라모비치는 왜 자신의 퍼포먼스를 사진으로 기록했으며, 사진이 퍼포먼스 작품을 대리하는 것을 용인했을까? 이런 매체의 전환을 어느 누가 정한 것일까? 이런 것은 미술의 관례일까?

연극계에서는 왜 연극을 소장하려 하지 않을까? 물론 공연계에서 중요하다고 판단되는 연극, 무용 등의 행위중심의 작품을 동영상으로 기록하여 학문적, 교육적 목적으로 소장하지만 미술과 같이 작품의 원본으로 대접하지는 않는다. 그런데 왜 미술은 연극과 같은 행위 중심의 작품을 원본 그대로 보존하려고 하는 것인가? 연극과 같이 행위가 반복되는 것이 아닌 일회성, 단 한번의 행위라면 그것은 연극과 달리 보존할 가치가 있을 것이다. 그러나 연극과 같이 반복이 가능한 작품을 연극과는 달리 사진이나 비디오라는 다른 매체를 통해서라도 보존하려는 목적은 무엇인가?

그렇다면 아브라모비치의 퍼포먼스 작품이 구겐하임 미술관에 소장된 것은 원본으로 인정한 것이 아닌 학문, 교육적 목적으로 수집된 것인가?

질문 2.

윤리적 정치성 Ethical Politics

사람들을 구체적으로 조명하거나, 한 집단의 내러티브를 주목할 때 미술가들은 퍼포먼스가 아닌 카메라를 매체로 하여 비디오 작품을 완성했다. 비디오 작품은 영상 자체에 대한 실험이 빈번했던 60 70년대와는 달리 90년대가 지나자 미술가들은 지역적이고 사회적인 문제를 정치적 입장을 통해 표현하기 시작했다. 지구화와 다원주의를 통해 세상을 바라보기 시작한 미술가들은 보다 정치적이 되었고, 매우 구체적인 사건을 통해 자신의 입장을 시각화했다. 이렇게 현실적 내용을 담다 보니 당시 영상에는 많은 사람들이 등장했다. 영화와 같은 허구적 배경을 가진 영상부터 실제 사람을 대상화한 인터뷰와 같은 다큐멘터리형 영상까지 다양하게 나타나기 시작했다. 간혹 일부 영상작품은 사람들을 대상화 할 뿐, 사람들을 주체화시키지 못했다. 이런 류의 작품은 실제 사람들과 공동으로 영상을 만들거나, 사람들과 같이 행동한 내용을 기록하여 공동의 저작권을 갖는 것이 아닌, 미술가의 권위(authority)가 여전히 강력하게 자리한 영상들이었다. 영상에서 사람들은 실재하지 못하고 여전히 소재화되어 대상으로 머물렀다.

시린 네샤트의 작품은 이슬람 국가의 정치적, 문화적 불평등과 차별 받는 여성과 이란 문화의 부조리에 대한 간접적 비판이다. 네샤트의 사진과 동영상에는 얼굴과 몸을 차도르로 감싼 이슬람 여성이 빈번히 등장하는데, 이들은 이슬람의 역사로 인한 여성에 대한 차별적 인식을 비판하기 위한 소재로 등장한다. 사진과 비디오 작품에 등장하는 다수의 이란 사람들을 보다 보면 즉각적으로 몇 가지 궁금증이 생긴다. 차도르 여인들은 네샤트의 작품과 동일화를 이룰 적절한 조건에 따라 참여했던 것일까, 여인들은 네샤트의 의도를 이해하고, 자발적으로 참여한 능동적 주체였나, 이들의 현재 상황은 영상에 출연한 이전의 시기와 비교하여 변화가 일어났는가, 이들은 이 작품이 국제적으로 주목을 받고 명성을 갖게 된 것을 알고 있는가 하는 의문들이 그것이다. 미국 캘리포니아에서 성장기의 대부분을 보낸 네샤트는 이란 태생이고 이슬람의 피를 갖고 태어났다는 사실로 인해 이슬람 문제를 비판할 수 있는 자격을 부여받았다고 말할 수 없다. 네샤트는 실제 이란에서 성장하지 않았기에 정확하게는 이방인으로 간주될 가능성이 있지만, 이슬람 문제에 대해 타인종, 타국적자, 타종교인이 언급하는 것보다는 훨씬 자연스럽게 비춰질 수 있다. 하지만 그녀의 정치적 올바름에도 불구하고 그 올바름을 위해 소재화된 사람들과 대상화된 환경이 그 영상 작품에서 독립된 주체의 역할을 하는지 의심스럽다.

다큐멘터리 영상에 등장하는 사람들은 상상의 텍스트가 아닌 현실을 기반으로 나타난다. 따라서 실재하는 사람들이 뿜어내는 아우라가 영상물을 기획하고 제작한 작가와 동등한 힘을 갖을 수 있다. 허구의 내러티브를 기반으로 배우들에 의해 구성되는 영상과 실제 사람들에 의해 펼쳐지는 영상의 차이는 단순히 형식적 차이가 있는 것이 아니라 그 영상의 지적 권리에서 차이가 나타난다. 후자의 경우, 연출가와 실제 사람들의 권리는 동등하다.

‘미술 제작에 참여하는 사람들’이 아닌 ‘미술 작품에 참여하는 사람들’은 다르게 구분된다. 네샤트 작품에 등장하는 사람들은 영상 제작을 위해 동원된 사람들이 아닌 출연자들이다. 네샤트의 영상작품의 저작권은 네샤트에 귀속되기 때문에 영상에 등장하는 사람들은 출연자로 정의되고 작가와 출연자와의 관계는 인건비, 또는 사례비라는 형식을 통해 이들 간의 경제적 관계는 정리될 수 있다. 그러나 이 작품이 명성을 얻게 될 때, 영광은 작가에게 돌아가고 그들은 언제나 자신들이 있던 곳에 그대로 머물러 있게 되는 위계적이고 불평등한 상황이 발생한다. 영상작품이 영화와 다른 점은 바로 이 지점에 있다. 아울러 다큐멘터리 영상과도 다른 지점에서 불완전한 상황은 일어난다. 저작권과 소유권이 영상 작품을 만든 작가에게 있다는 것은 법해석상 아무런 문제가 있지 않으나, 윤리적으로 불편해지는 것은 지적 재산이 작가에게 속하게 만들어 준 사람들의 협력과 지적 재산을 통해 큰 명성을 얻게 된 작가의 ‘위치’때문이다.

미술가가 등장한 퍼포먼스가 아닌, 미술가에 의해 기획된, 그리고 참여자들에 의해 완성된 퍼포먼스는 미술가의 아이디어라는 이유로 이 작품의 저작권은 미술가 개인에게 귀속된다. 이때 특정분야의 전문가가 노동자로 분류되는지, 단순 참가에 의한 지원자로 분류되는지는 미술가와 참가자 사이에 명확한 합의가 없다면 정확히 알 수 없다. 노동자로 분류가 될 경우, 단순히 노동 시간에 비례한 임금계산으로 끝난다고 하는 것은 참여자의 전문성의 강도가 높다면 올바른 판단이 아니다. 다큐멘터리, 인류학자의 사진 기록과 같은 전문적 연구의 결과는 결과물에 등장하는 인물들에 비해 우위성을 가진다는 인식이 지배적이었던 것은 아닐까?

정동노동(affective labor)이란 노동자의 감정을 관리, 통제함으로써 수행되는 노동인 동시에, 인간적 교류를 촉발하고 확대할 수 있는 노동 양식이다. 가수로 데뷔하려는 사람들은 육체, 정신, 감정을 모두 자원으로 활용해 강도 높은 노동을 수행하며, 이를 촉진하는 노동윤리는 경쟁의 윤리와 연대의 윤리이다. 티노 세갈(Tino Sehgal)의 퍼포먼스에 등장하는 대부분의 퍼포머는 무용가이거나 그에 준하는 전문성을 가진 사람들이다. 이들이 행하는 노동은 노동 윤리로서의 연대와 효율적 팀워크를 위한 것만이 아니라 그들이 정동노동을 통해 인간관계를 확대하는 노동자이기 때문에 그들의 노동(행위)에 스며들어 있다. 인간적 행위가 도구적 측면을 갖듯 도구적 행위도 인간적 측면을 가지며, 이 인간적 측면을 드러내는 것이 중요한 과제가 아닐까?

인물 다큐멘터리와 같은 비디오 영상 작품에서 주된 역할의 인물이 있다하더라도 작품의 저작권 및 소유권은 작가에게만 전적으로 귀속되는 것이 타당한가? (법적으로 문제가 없다 하더라도)

질문 3.

저작권 분할 Division of copyright

우리는 미술작품을 문화적 자산으로 받아들인다. 동시에 미술작품이 상업적으로 거래가 된다는 것도 알고 있다. 작품가격이 궁금하다는 것은 작품이 상품으로서 교환이 가능하다는 것을 알고 있다는 것을 뜻한다. 미술관의 기획전과 비엔날레에 전시된 작품을 보면 그 작품을 만든 미술가는 물론이고 전시를 만든 모든 사람들이 동시대 중요한 사회, 문화적 이슈를 책임감 있게 다루고 있다는 것을 알 수 있다. 이런 공공적 책임이 미술작품은 문화적 자산이자 공공재라고 인식하게 해준다. 현대의 대부분의 미술작품은 오늘은 미술관에서, 내일은 아트 페어(art fair)에서 전시되고 있다. 같은 작품이지만 미술관에 있을 때는 문화 자산이자 공공재이고, 화랑으로 옮겨오면 상품이자 개인 소유물이 된다. 이런 일은 인접 예술분야에서는 발견하기 힘든 일이다. 연극이 극장에서 공연된 후, 공연 시장에서 그 연극이 팔리는 일은 있을 수 없는 일이기 때문이다. 그러나 유독 미술에서 이런 일이 벌어지는 것은 미술이 전통적으로 물질을 다루었기 때문이다. 시각예술은 회화, 조각, 공예를 말하며 사진, 심지어 비디오의 경우도 여기에 해당된다. 모더니즘 이후 미술작품은 상품으로서 기능하게 되었다. 미술관에서는 작품 수집을 통해 당대의 중요한 미술작품을 소장하고 이를 대중에게 공개하는데 비해 화랑은 미술작품에 가격을 매기고 이를 상품화했다.

퍼포먼스와 같이 물질화 되기 어려운 작품은 오랫동안 상품으로서 외면 받아왔으나 미술사적 가치가 있다면 미술관에서는 퍼포먼스는 물론이고 비물질적인 모든 유형의 작품도 소장했다. 가치가 인정되면 미술관은 연극적 형태의 퍼포먼스라도 소장했는데 비해 연극계에서는 왜 연극을 소장하려 하지 않을까? 물론 공연계에서 중요하다고 판단되는 연극, 무용 등의 행위중심의 작품을 동영상으로 기록하여 학문적, 교육적 목적으로 보존했지만 미술과 같이 작품의 원본으로 대접하지는 않았다. 그러나 미술계에서는 퍼포먼스 그 자체를 소장할 수 없기 때문에 다른 매체로 기록된 것을 소장하면서 이를 작품의 대표성을 인정하는 원본으로 대접했다. 이런 과정은 모순이라고 볼 수밖에 없다.

작가가 직접 퍼포먼스를 하는 경우가 아닌 다른 이들에 의해 퍼포먼스가 진행될 때 몇가지 까다로운 문제가 발생한다. 퍼포먼스에 참여한 사람들은 보통 사람들일 수도 있고, 어느 특정 분야의 전문가들일 수도 있다. 협업으로 진행될 때도 있고, 임시로 고용된 형태로 진행될 때도 있다. 이들이 지원자(volunteer)로 분류될 수도 있고, 이들이 보인 전문성에 대해서는 사례비(honorarium)라는 항목으로 지불하기도 한다. 경우에 따라 사례비가 아닌 인건비로 계산하여 임금을 지불할 수도 있다. 퍼포먼스에 참여하는 사람들은 작품 제작에 참여한 조수(assistant)나 일용직 노동자와 같이 물질을 생산하는데 도움을 준 것이 아니라 사람으로 참여하여 자신의 모습, 행위등을 주체화한다. 만약 퍼포먼스가 화랑을 통해 상업적 거래가 생긴다면 우리는 퍼포먼스를 상품이라고 부를 수 있을까? 사람 자체는 상품으로 간주할 수 없기 때문에 퍼포먼스를 촬영한 비디오를 상품으로 간주해야 하는가? 비디오 기록이 상품으로써 가치가 있는 것인가? 퍼포먼스는 어떻게 상품으로 기능할 수 있는가?

연극작품에서 배우들의 퍼포먼스는 상품이라고 규정할 수 없다. 배우들의 연기(행위)는 인건비와 같은 개런티(guarantee)로 수치화된다. 인건비가 그들의 육체적, 정신적 노동(창작성)을 대변하는 셈이다. 연극은 공동의 총체적 작품이다. 그래서 퍼포먼스만을 따로 떼어 놓고 극을 평가하기란 불가능하다. 그래서 연극은 단 사람만의 지적 재산으로 간주할 수 없다. 그러나 퍼포먼스 자체는 미술가 개인의 지적 재산으로 간주된다. 퍼포먼스는 연극과 달리 미술관에 소장되거나 화랑에서 판매된다는 점에서 그 최종 형태가 중요하다. 그러나 사람들이 참여한 이 상황이 실제로 미술관에 수집된 적은 없다. 단지 윤리적인 문제 때문이 아니라 현실적으로 사람들 소장할 수 없기 때문이다. 그러나 티노 세갈이라는 미술가에 의해 하나의 퍼포먼스가 미술관에 소장할 수 있는 경이로운 일이 벌어지게 되었다.

미술작품은 공공재이기도 하고 동시에 상품이기도 한 이중적 척도는 언제부터 어떤 과정을 통해 합의되었는가?

질문 4.

지시된 상황 Instructed Situation

티노 세갈의 퍼포먼스 ‘구성된 상황’은 작가 자신이 작품에 출연하지 않는다. 그는 다른 이들을 작품에 참여시키고 그들에 의해 행위가 벌어진다. 만약 같은 작품이 다른 장소, 다른 시기에 벌어진다 하더라도 다른 사람들에 의해 유사하게 그 행위가 전개된다. 마치 연극과 같이 동일한 작품이 동일하게 전개될 수 있는 이유는 퍼포머들에게 제공된 설명서(지시문 instruction) 때문이다. 티노 세갈은 퍼포머에게 이메일로, 혹은 전화로 그들이 행해야 할 내용을 알려주고 지시한다. 이 ‘설명’을 통해 모든 유형의 ‘상황’적 작품은 다시 재현 가능 해졌다. 그렇다면 ‘상황’이라고 구분되는 이러한 표현 형태가 티노 세갈에 의해 발명되었을까? 티노 세갈은 퍼포먼스를 ‘구성된 상황’으로 규정했지만, 퍼포먼스 뿐만 아니라 미술화되기 어려운 모든 유형의 애매한 작품은 ‘상황’으로 정리하면 이해가 아주 쉬워진다. 예를 들어 아르테 포베라 작가로 알려진 야니스 코넬리우스(Jannis Kounellis)의 1967년 작품 무제(카발리)(Untitled (Cavalli))는 갤러리에서 건초를 먹고 있는 실제 살아 있는 말 12마리이다. 이 작품은 매우 도발적으로 보이는데 살아 있는 동물을 미술 작품이라고 선언하는 그의 야심 찬 도전 때문일 것이다. 마르셀 뒤상의 기성품과는 달리 살아있는 동물을 제시했다는 것은 아르테 포베라의 정신을 계승하면서 동시에 상업주의 물질적 재료에 거부의 뜻을 보이는 것이기도 했다.

그러나 예상치 못한 곳, 도시에 위치한 갤러리 내부에서 커다란 말 12마리를 맞닥뜨리게 되는 의외의 공간, 공간 안에 스며든 동물과 건초 냄새, 이런 상황이 어떻게 미술로 규정될 수 있을까? 미술작품이라면 살아있는 생명체인 ‘말들’은 어떻게 미술관에 소장될 수 있을까? 소장될 경우, 단지 지시사항이 적시된 설명문과 기록 사진만으로 대체되어 소장되는 것일까? 그러나 지시사항이 적힌 설명서가 어찌 실제 말을 대신할 수 있다는 것인가?

관점을 바꾸어 이 작품을 설치작품이나 해프닝으로 보기 보다는 ‘지시된 상황’의 작품으로 받아들인다면 이 작품이 다른 곳, 다른 시기에 재현되는데 문제가 생기지 않는다. 설명서에 적힌 대로 이행한다면 12마리의 말을 각기 다른 시기에 서울에서도, 뉴델리에서도, 코펜하겐에서도 볼 수 있게 된다. 심지어 동일한 제목으로 다시 재현될 수 있다. 실제로 이 작품은 2006년 아트페어 쾰른(Art Cologne 2006)에서 다시 재현되었다.

![]()

Jannis Kounellis, Untitled (Cavalli), 1967, 12 horses, installation view at Galleria L’attico, Rome, 1969

![]()

Jannis Kounellis, Untitled (12 Horses), 2015.

A NYC art gallery displayed 12 live horses for four days

갤러리에 있는 12마리의 말들은 4 일 동안, 매일 6 시간에서 9 시간 동안 벽에 묶여 있었다. 그런 이유로 자유롭게 움직일 수 없었을 뿐 아니라 누워 있거나 가려운 곳을 긁지도 못했다. 갤러리는 말들이 음식, 물, 에어컨을 통해 인도적으로 취급되고 있다고 말했으나 그것이 사실이라 할지라도 예술을 위해 동물을 소품이나 물체로 간주한 이 행위에 대해 변명할 거리는 없어 보였다. 결국 예술의 표현을 위해 동물을 학대하는 잔인하고 비인도적인 행위라는 비난만 받고 전시는 곧 철수되었다.

김홍석의 작품 <Eyes Wide Shut>의 경우도 이에 해당한다. 백색 방에 강한 조명이 온 방을 비추는 것이 전부인 이 작품은 미술관에서 설치작품으로 분류되었다. 그러나 이 작품이 미술관에서 소장이 결정되었을 때 김홍석은 조명기를 제공하는 것이 부질없음을 미술관에 설명해야 했다. 미술관은 이를 이해했고, 결국 미술관은 ‘빛’을 소장하게 된 셈이었다. 이 과정에서 김홍석은 30평방미터, 50평방 미터, 100평방미터일 경우, 조명기의 종류, 수량, 조명기 위치, 조명기 밝기 등이 명시된 설명서를 제공했다. 미술관은 김홍석의 작품을 전시할 경우, 설명서대로 다시 재현하면 이 작품의 원본을 다시 보일 수 있게 된 셈이다.

![]()

눈 크게 감고 Eyes Wide Shut, 2001

Installed at Art Sonje Center, Seoul in 2009

이렇게 ‘설명’이 작품을 부활시킬 수 있는 가능성으로 제안된 것은 이미 펠리스 곤잘레스 토레스(Felix Gonzalez-Torres)로부터 구체화되기 시작했다. 그는 사탕, 조명, 종이 더미 등과 같은 일상의 사물을 전시장에 설치했는데 그가 설치 장소에 직접 오지 않더라도 작품의 설치가 완성될 수 있다는 점을 제시했다. 사탕이나 조명기의 경우, 실제 설치를 책임 질 사람이 임의대로 결정하여 설치하면 곤잘레스 토레스의 작품이 되었다. 조명기를 천장에 치렁치렁 매달거나 바닥에 늘어뜨리거나 하는 정도의 지시만 내려지면 전시가 있는 지역에서 구입된 조명기로 설치하면 곧 그의 작품이 된 것이다. 그 이유는 그가 그렇게 해도 된다고 하는 지시에서 비롯된 것이다. 그의 이런 허락은 사실 작가주의에 매몰된 사람들의 입장에서는 이해가 어렵지만, 조명기를 천장에 늘어뜨리는 일과 사탕을 수북하게 전시장 바닥에 쌓는 일은 미술가의 세심한 손길이나 예리한 시각이 아니어도 누구나 실현시킬 수 있는 것이어서 굳이 전문가의 도움이 필요하지 않았다. 이로서 미술관에 설치를 책임 진 익명의 한 개인은 곤잘레스 토레스의 지시문의 두번째 해석을 담당하고, 그에 의해 형상화된 작품은 장소의 특정적 주체성을 강화시킬 수 있게 된 것이다. 곧 곤잘레스 토레스의 작품의 고유성을 유지하면서도 완전히 다른 독자적 주체가 탄생한 것이다. 아무리 지시문에 의해 다시 발생한다고 하더라도 이러한 논리에 의해 이 작품은 각기 다른 장소에서, 각기 다른 해석으로 태어날 수 있는 괴물이 된 것이다. 물론 그 독립적 작품은 곤잘레스 토레스의 이름 아래 전시된다. 그의 설치 작품은 ‘상황’이 아닌 ‘설명(지시)’으로 작동되었다.

![]()

Untitled(North), 1993

![]()

Untitled(North), 2012, Plateau, Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul

![]()

![]()

Untitled (Stockholm) 1992, Stockholm Kontshall, Stockholm, Sweden. Installation view: MMK Untitled (For Stockholm) 1992

그로 인해 많은 것들이 미술작품이 될 가능성을 얻게 되었다. 그러나 작가의 권위, 현전성을 중요하게 생각하는 사람이라면 어느 누구도 이런 상태의 작품을 작품으로 받아들이기 어려울 수 있다. 곤잘레스 토레스가 지시한 (또는 재료 구입 및 설치를 허가한) 작품은 다른 누군가도 거의 동일하게 재현할 수 있다. 물론 작가의 증서(certificate)가 있는 작품과 아닌 것에는 커다란 차이가 있지만 곤잘레스 토레스의 작품을 알고 있는 어느 카페 주인이 자신의 카페에 이 작품을 똑같이 재현했을 경우, 작품의 권위를 존중하는 이들의 입장에서는 매우 당황스러울 수 있다.

![]()

도표 1-1. <지시된 상황>-미술작품의 생산, 유통, 전시의 관계에 대한 도식

![]()

도표 1-2. 미술작품의 생산, 유통, 전시의 관계에 대한 도식

곤잘레스 토레스의 작품에서 사람들은 작품을 관람하는 것이 아니라 사탕, 포스터등과 같은 그의 작품을 가지고 간다. 물건은 사라지고 사람들의 참여가 작품을 완성하게 하는 것이다. 미술관에서 이 작품을 소장할 때 ‘지시된 상황’대로 사탕을 바닥에 깔고, 종이 포스터를 쌓아 두고 관람객을 기다리면 그의 작품을 복원한 것으로 보아도 되는 것일까? 다른 퍼포먼스 작품처럼 사진 기록으로는 이 작품을 대체할 수 없기 때문에 이런 전시 형태가 그의 작품을 대표하는 것이라고 사회적 합의를 이룬 것일까?

구성된 상황 Constructed Situation

2000년대로 들어서자 티노 세갈(Tino Sehgal)이라는 퍼포먼스 미술가에 의해 퍼포먼스에 대한 분류가 보다 더 원론적으로 돌아갔다. 그는 자신의 퍼포먼스를 시간성의 행위보다는 ‘구성된 상황(Constructed Situation)’이라고 불렀다. 티노 세갈은 퍼포먼스는 다른 매체로 대체될 수 없으며, 다른 매체로 대표된 것은 퍼포먼스가 될 수 없다고 주장한 셈이다. 사실 그의 주장은 아주 타당하다. 그럼에도 불구하고 미술계에서 퍼포먼스를 비디오 작품으로 대체한 것은 역사와 교육에 대한 보존 때문이었다. 이것은 서구의 윤리적 인식 체계에서는 매우 올바른 일이다. 티노 세갈의 결정은 옳지만 이미 이미지의 시대로 접어든 사회에서 이를 받아들이는 것은 불가능했다. 그럼에도 불구하고 이런 점을 굳이 다시 들춰내어 기존 인식의 체계를 흔드는 일은 분명 필요한 것이었다. 왜냐하면 이런 과정이 없다면 어떠한 유형의 사회적 문제 제기나 이로 인한 인식의 충돌에 대해 대응할 시도조차 할 수 없는 것과 같기 때문이다.

허쉬 호른 미술관(Hirshhorn Museum)은 티노 세갈의 2006년 작품인 ‘This You’를 계약서, 사진 또는 해당 저작물에 대한 문서없이 구입했다. 이 매입 과정에서 미술가를 대리한 공증인은 티노 세갈이 제공한 규정을 설명하는 것으로 시작해서 결국 구두 계약으로만 작품 매매가 이루어 졌다. 이 과정은 말 그대로 대화라는 것이 계약과 매매의 실제 모습이었다는 것을 의미한다. 이로써 문서 없이 작품이 거래된 첫번째 사례가 생겼으며, 비디오나 사진, 종이에 인쇄된 텍스트가 아닌 순수한 비물질의 상태의 작품이 판매된 첫번째 사례이기도 했다. 이것은 미술가들에게 확장된 인식을 확인시켜준 혁명적인 일이었으나 이 일은 미술가의 해방보다는 화랑의 상업적 거래를 확장시켜 준 일이기도 했다. 물론 대다수의 미술관은 여전히 문서를 요구하지만, 영상 기록조차 대체하지 않은 말 그대로 ‘있는 그대로’의 퍼포먼스를 구매할 수 있다는 가능성은 라이브아트(Live Art)라고 명명된 행위 중심의 미술이 아트마켓에서 한 섹션으로 자리하여 활발히 거래를 할 수 있는 현실로 이어주었다.

티노 세갈의 ‘상황’은 배우, 전문가, 혹은 비전문가, 댄서, 그리고 대중이 섞여 들어, 경비원이 방문객의 일부가 되고, 커플이 열정적으로 포옹하는 것과 같은 일상의 모습이 특수한 공간에서 벌어진다. 여기에서 작가가 사진을 찍도록 하였다면 마치 1960년대 해프닝을 연상케 했을 것이다. 하지만 전혀 그렇지 않았다. 사진, 비디오 촬영은 금지되었다. 모든 것은 소문으로 전해졌다. 그의 작품에 대한 소개를 하려해도 사진이 제공되지 않으니 설명도 없을 수 밖에 없었다. 2010년 퐁피두 센터가 그의 작품을 구매할 때는 어쩔 수 없이 간략한 설명은 있긴 했었다.

문제작인 <이 상황 This Situation>은 2009년 2월, 마리안 굿맨 갤러리(Marian Goodman Gallery)에서 발표되었다. 당시 ‘역할을 맡은 사람’은 고차원적인 철학적 토론을 통해 관객을 끌어들였다. 그들은 모두 지성인, 대학생들이었으며 작가와 함께 논의한바 있던 과학자들이었다. 그런 것이 상황을 만들었다. 어떤 상황을 만드는 것이 그들의 임무였기 때문에 부끄러움 없이 연기를 펼치는 것이 이상할 것이 없었다. 하지만 지성인들은 조롱 섞인 태도를 보이며 불편해 하였고 선입관에 벗어나지 못한 채 논쟁을 이어 나갔다.

‘상황’이란 무엇인가? 세미나인가? 심리치료인가? 고해인가? 지식인의 사교 모임인가? 무지한 사람이 티노 세갈의 퍼포먼스에 있었다면 이러한 질문에 답을 하려고 했는지도 모른다. 왜냐하면 일관성 없는 대화와 끔찍한 울음소리, 그리고 <이 상황 This Situation>속 ‘역할자’들의 미스테리한 자세 때문에 이해하기가 쉽지 않기 때문이다. 하지만 다행히, 미술관은 그들의 문화유산을 위해서 무지한 사람들을 고용하지 않았다. 그리고 그 때문에 퐁피두 센터가 <상황 The Situation>을 구매하는 데 고가를 치른 것이다. 티노 세갈은 미술관에 구두로 된 ‘지시(설명)’ 밖에 판매한 것이 없다는 것이었다. 이 작품의 이례적인 특성에 따라 <상황 The Situation>의 재현이나 재생산은 불가능하다는 것이었다. 퐁피두 센터는 아무것도 구매한 것 없이, 납세만 하느라 비용을 지출한 셈인 것이었다. 이 사건을 통해 <이 상황 This Situation>의 구매조건 뿐 아니라 연출에 대해서도 다시 보게 되는 계기가 되었다. 티노 세갈은 이 작품의 퍼포먼스 자체보다 ‘비구매’의 의미를 대중이 이해할 수 있도록 중점을 두면서 시작했다. <상황 The Situation>의 행위들을 구매한다는 것은 불가능하다. 하지만 그는 “이 작품을 완성하기 위해, 미완성에서 벗어나기 위해, 이 작품이 실현되기 위해 미술관은 ‘아무것도 아님’을 구매해야 할 것이다.”라고 말한다.

우리는 티노 세갈과 ‘역할자’의 관계가 궁금하다. 티노 세갈은 ‘역할자’들을 그냥 내버려두었을 거라고는 아무도 생각하지 않지만 어떤 지시 혹은 어떤 임무를 주었는지에 대해서는 잘 알지 못한다. 그들의 이름이 어디에도 없었고, 비평가들조차 전문배우라고 생각했기 때문에 아무도 그들이 누구인지는 알지 못했다. 퍼포먼스가 비밀리에 진행되었기에, 역할자들이 자연스럽게 한 것인지 연출된 것인지 알 수 없었다. 그들의 일시적 대화에서 문화적 성찰같은 것이 보였지만 미리 준비된 것인지 아니면 임기응변인지 알 수 없었다. 그래서 사람들은, 배우라기보다, 지성인이나 교수들, 아니면 인간 과학 분야의 전문가들로 보였다. 그들의 고용조건은 현대예술이 취하는 어떠한 방법도 나타내지 말라는 것이었다. 그들은 티노 세갈의 요구조건이 꽤 까다로웠음에도 불구하고, 가정부와 비슷한 급료에 만족하였다. 영예로움은 무엇보다 강한 보상이었던 것이다.

티노 세갈의 퍼포먼스에서 퍼포머에게 지급되는 재화는 일종의 사례비로 간주된다. 사례비조차 받지 않고 자발적으로 참여한 사람들도 있기 때문에 그의 작품에서 미술가의 의도와 참여한 퍼포머 간의 윤리적 문제는 없을 지도 모른다.

티노 세갈의 작품이 미술관에 소장되었다는 것은 기부가 아닌 이상 재화로 환원되었다는 것을 뜻한다. 티노 세갈의 작품에 참여한 퍼포머의 행위는 비영리, 자발적 참여라고 하는 부류와 금전적 보상을 통해 퍼포머의 행위가 그의 작품에 귀속되는 것은 인정하는 부류로 나뉠 수 있을 것이다. 금전적 보상을 통해 퍼포머의 행위가 그의 작품에 귀속되는 것은 인정하는 부류라 할지라도 과연 자신들의 행위가 백퍼센트 미술가의 지적 재산권에 포함된다는 것을 받아들일 수 있는 것일까? 티노 세갈의 작품을 미술관이 취득했다는 것은 퍼포머의 행위를 구입했다는 것도 포함된다. 이때 이 작품이 다시 재현된다면, 퍼포머는 누구여도 되는, 미술관이 지정해 준 사람이기만 하면 가능하다는 것을 인정하는 셈이다. 그러나 퍼포머의 행위와 그 존재가 티노 세갈의 작품에서 중요한 요소라는 것을 인정한다면, 그의 작품이 판매되는 일은 윤리적으로 자유로울 수 없게 된다. 그러나 이런 일은 미술에서 이미 무수히 일어났다. 그렇다면 우리는 퍼포먼스의 참여자(퍼포머)의 전문성, 자발성이 퍼포먼스를 기획한 작가의 저작권에 포함될 뿐만 아니라 그들의 행위가 부지불식간에 사라져 미술가의 권위 속으로 사라지는 것이 타당한 것으로 인정해야 한다.

윤리는 ‘선언되는 것’이 아니라 ‘논의되어야 하는 어떤 것’이다. 윤리는 ‘선험적 진리’가 아니라 ‘학습된 실천’이기 때문이다.

티노 세갈은 자신의 작품을 미술관에 판매했다. 미술관이 그의 작품을 대중에게 전시하려 한다면 그의 지시대로 퍼포머가 등장하여 지정된 장소에서 행위를 보일 것이다. 또한 그의 개념대로 우리는 어떤 영상적 기록도, 출판 및 다른 매체적 기록을 통해 그의 작품을 접할 수 없다. 따라서 그의 작품을 보고자 한다면 그의 작품을 소장한 미술관에 가서 지정된 상연 시간에 봐야 한다. 이것은 공공재로써 미술의 역할을 제대로 하는 것일까? 그의 개념을 존중하여 꼭 그 장소에 가야 하는 것인가? 서울에 사는 내가 베를린에 가야 하는 것인가? 공공재를 거부하고 개인의 표현이라고 하면 용인될 수 있다는 것은 우리가 합의한 인식체계인가?

질문 5.

현실 재현을 위한 플랫폼 Platform for the reenactment of reality

현실도, 연극도, 퍼포먼스도 아닌 Neither reality, theatre nor performance